by Juan Molina

by Juan Molina The oriental hornet (Vespa orientalis) is a type of vespid native to tropical and temperate areas of Central Asia, the Middle East and countries in south-eastern Europe, including Mediterranean countries such as Albania, Greece, Italy and Malta.

It was first seen in Valencia on the Iberian Peninsula in 2012, but it did not establish itself as it did not survive the winter. Six years later, in 2018, it was first sighted in the important port city of Algeciras, Cadiz, from where, this time, it began a progressive expansion in the following years.1 V. orientalis has also been spotted in France (Marseille in 2021, and two neighboring departments in 2023).

It does not seem a coincidence that both entries have occurred next to important ports where the arrival of goods is constant. Its adaptation to the warm and dry climate has favored its rapid spread in the south of the Iberian Peninsula.

V. orientalis is a eusocial insect, living in colonies created by a fertilized reproductive female that emerges from hibernation in spring and generally finds a nest in a hollow in the ground or in walls, which grows over the weeks. Once developed, the worker population is considerable and from then on it is these that are responsible for finding food and bringing it to the nest to feed the larvae of subsequent generations. At the end of summer or the beginning of autumn, the new reproductive females emerge and are fertilized and later, with the drop in temperature, these females take refuge in cracks or hollows to hibernate until the following spring.

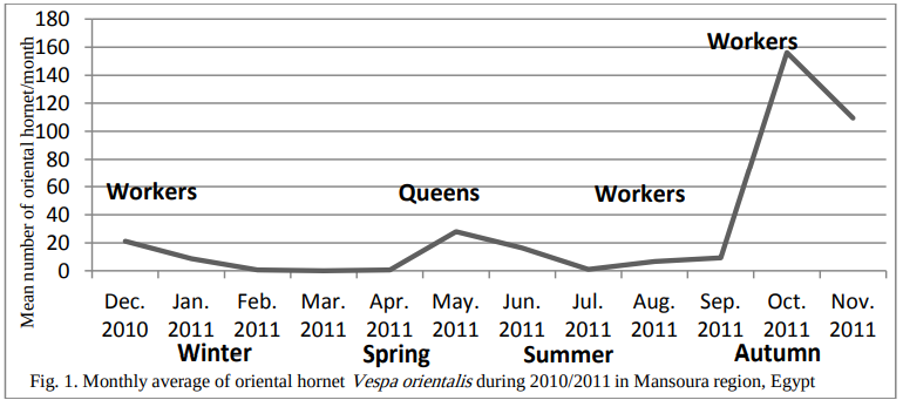

Studies carried out in Egypt revealed that the maximum predatory activity is carried out at a temperature of 24.4ºC and relative humidity of 69.5% and at 17.3ºC and humidity of 79%. A maximum of foraging workers was also observed in October and a second peak of population in November. For their part, queens begin to be detected in the last week of April and continue to emerge until July (Taha, 2013).2 Another investigation carried out by Shoreit (1998) detected foundress queens between January and May, with a maximum activity in March.3 The discrepancies in findings among various researchers could be attributed to year-to-year climatic fluctuations and the overall trend towards milder winters observed since the turn of the 21st century.

Many insect species begin their activity depending on the temperature, for example the reproductive of Vespa velutina a species of vespid with many similarities) come out of winter dormancy when the minimum temperatures are higher than 10ºC (Monceau et al. 2012).4

Preferences have also been observed in terms of hunting departure times. In the northern Sinai region, no predatory activity on hives was observed before 9 am or later than 3 pm, with the hours of maximum hornet population being between 9 am and noon. The largest number of hornets was detected in September, and in the following months they observed that later hunting habits were adopted, between noon and 6pm (Mahfouz, 2022).5

This increase in activity at the end of summer is due to the fact that during this time the male hornets are born and fertilize the females, future founders of the nests the following spring.

Changes in the climatic conditions of some regions towards milder winters and a longer summer season facilitate the expansion of this species to new regions (Mahfouz, 2022).5

In countries such as Egypt, the oriental hornet is the most important predator of bees, causing damage to honey production and problems with crop pollination. But they also have an effect on agricultural production by feeding on grapes, dates and other fruit trees, causing considerable economic losses.6

Colonies of vespids near apiaries exert a continuous predatory action on bees in the vicinity of hives and watering troughs, causing depopulation at a critical time for the bee colony.

In addition, when bees detect predators near the hive, they are inhibited from going out to forage. The presence of 10 hornets in front of the entrances is enough to reduce the foraging activity of bees by 60 to 100%.7 This cessation of foraging results in a progressive state of malnutrition and oxidative stress due to the permanent state of alert of the colony.

But hornets intruding into a hive can also be vectors transmitting viral diseases: a study carried out in Italy by P. Zucca in 2023 revealed the presence of DWV, BQCV and SBV among others.8

In total, losses of honey bee colonies in Egypt attributable to V. orientalis have been observed, ranging from 18.6% to 44.2% (Mahfouz, 2022)5 although other authors (Al-Fattah, 2009)9 counted 50% of dead hives.

Oriental hornet builds nests in holes, in walls, cavities and abandoned burrows of other animals. The nests are relatively difficult to identify because they have an entrance that goes unnoticed; this is precisely where one of their dangers lies. People who like to walk in the countryside can get too close to a nest, giving rise to a defensive response. Its sting is very painful and causes intense pain that extends beyond the point of inoculation. It can cause general malaise, dizziness and fever in non-allergic people, and much more severe symptoms in those who are allergic. The sensation of pain and subcutaneous oedema persists for days, and the time of total remission of symptoms can last up to 2 weeks (Zucca, 2023).8 The uncontrolled expansion of this species, which finds a favorable ecological niche and is initially devoid of predators, is becoming inevitable and unstoppable and also poses a risk to public health.

Despite being a problem that, as we have seen, transcends livestock activity, it is the beekeeper who suffers the greatest losses and who has no other choice but to try to reduce the effects of the presence of hornets in their hives.

There are several strategies that, within the framework of an integrated fight, we must implement as many as possible, seeking the cumulative result of their partial effects (Sweelam, 2019).10

There are other control methods still under investigation, such as the use of repellents in hives based on cypress essential oil (Augul, 2023).12

Poison baits or adhesive sheets for rodents are generally prohibited due to their low selectivity and impact on other wild species.

A natural enemy of V. orientalis is also known, the parasitic wasp Sphecophaga vesparum Curtis (Havron, 1995)13 and bacteria that have confirmed their effect in controlling the nests of these insects such as Anthrax leucogaster and Pyemotes ventricosus (Wafa, 1968).14

Research is striving to develop attractants based on specific pheromones with which to capture the maximum number of hornets without toxic residues and without affecting the native fauna. Until we achieve this goal, we must do everything possible to maintain the well-being and production of our hives.

References :

by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma  by Juan Molina

by Juan Molina Join the Véto-pharma community and receive our quarterly newsletter as well as our occasional beekeeping news. You can unsubscribe at any time if our content does not suit you, and your data will never be transferred to a third party!

© 2019-2025, Véto-pharma. All rights reserved