by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma After the introduction of this new category in our newsletter in October, we were happy to receive very positive feedback in response to the first article of this series. Thank you for your kind words, we appreciate it! In our November case study, we will direct our attention to a common problem that is presented to us every year in slightly varying versions.

“My colonies are full of mites! I put the Apivar strips in the hives in August, and I left them in there for eight (8) weeks. I removed the strips a month ago, and now my hives are full of mites again. How is this possible?

I did not look at mite counts directly before and after treatment, but I saw lots of mites falling during the treatment – especially in the first few weeks.”

When we receive this kind of feedback from beekeepers, our goal is to understand what factors could have influenced their experience with the treatment. We then try to investigate various aspects surrounding the use of the product – how it was stored, handled, applied, and any other relevant circumstances – to piece together a clearer picture of the situation and identify potential contributing factors.

The beekeeper in this case was very forthcoming in sharing all the relevant information about his application with us. He had taken photos of the Apivar packs that he had purchased online: A 12-pack that was not expired (as indicated per the manufacturing date on the packaging, visible on the photos). The packaging was intact when he received the strips, and any other potential concerns about the product itself or the shipment and storage conditions it was exposed to were quickly ruled out.

We went forward by asking the beekeeper specific questions to help us clarify what had happened.

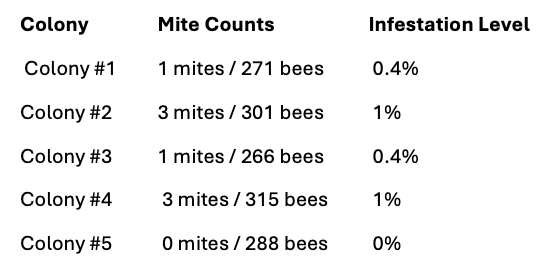

The first aspect that stood out here was the contradiction between the perceived high mite fall during the treatment and the fast re-infestation, just one month after the treatment. We asked the beekeeper when he had last treated against varroa mites before applying the Apivar strips in mid-August. The answer mostly ruled out concerns about a too steep build-up of the mite population before Apivar was used: “I treated them twice before this year… with formic acid. In March and in June”, is what the beekeeper told us. He also informed us that he did monitor his colonies for mite infestation rates in spring and after the second formic treatment in June. Out of his 10 colonies, he monitored 5. These were the alcohol wash results in the last week of June, after the formic acid treatment:

Looking at these results, it became clear that the observed percentage of infestation per 100 worker bees was very low for this time of the season (end of June), indicating the previous treatment had been successful. Between 0 and 1% infestation rate in late spring / early summer is considered below the treatment threshold.

The Veto-pharma team concluded that, “If the mite infestation rate was not out of control before the Apivar treatment, there are few alternative explanations to investigate that could explain the high mite load just one month after the Apivar treatment was finished”.

The first potential explanation brought us back to the term “re-infestation”. We were beginning to wonder whether:

Options a) and b) could be excluded immediately. The colonies had not been moved since May of the same year, and no new colonies had been added after spring. Regarding possibility no. 3, the beekeeper was quite sure from the beginning that no other beekeepers were around in at least a radius of 6-7 miles. He later confirmed that after reaching out to local landowners, in the meantime also treating his colonies again – this time with oxalic acid sublimation.

The second potential explanation had us focus on the application itself. We asked the beekeeper which dosage of strips he had applied, what hive type and hive configuration he was keeping his bees on, and if he had taken any other hive management actions during the 8-week Apivar treatment period.

In response, the beekeeper let us know that he “applied two (2) strips per brood box (or one (1) strip per five (5) Frames of Bees), just as recommended in the leaflet.” In addition, he was so kind to send us photos of a few opened hives with the Apivar strips in place – right after the application.

In this case, as in several other cases brought to us, the photos turned out to be a goldmine of information.

First, we learned that the beekeeper kept his bees on single deep Langstroth hives, and that he had indeed applied two (2) Apivar strips per brood box in each colony. However, we also noticed there was a second box on top of the brood box – at least on all the colonies that were visible in the photos. And we did not see any pictures in which Apivar strips were also applied in this upper box…

Upon closer inspection of the photos, we concluded that the upper boxes must be honey supers. The beekeeper confirmed this suspicion and explained to us: “I was not trying to collect honey from these supers. The honey in these boxes is a food source for the bees!” He then mentioned that he had observed his colonies were very strong at the beginning of August and decided that he would let his bees consume their own honey stores before he would offer additional carbohydrate feed later in the year. He also wanted to provide them with additional space before the colonies would eventually decrease their worker bee population in fall. Thus, he decided to put honey supers on top of the brood boxes and to feed the bees with sugar syrup. He left all the nectar and honey stores in the super as feed for his bees.

The Apivar label says that honey supers should not be set up on the hives during an Apivar treatment. On the other hand, adding honey supers during treatment exclusively as a food source for the bees is a bit of a grey zone. Clearly, the honey stored in these supers was not intended for human consumption. The most common questions that arise in this scenario are usually regarding the equipment and its future use. We recommend that honey supers which have been on the hives during treatment to feed bees should be thoroughly cleaned before they are used to collect honey for human consumption again. All the honey collected during an Apivar treatment must be removed before the same frames are used again to collect honey intended for human consumption in the following season. Ideally, the wax in those frames is renewed.

However, coming back to our main concern regarding the colonies’ varroa infestation rate: Could the addition of honey supers have contributed to the quick mite infestation increase after the Apivar treatment? Our first question to the beekeeper was: “Did you install queen excluders between the brood boxes and the supers?” And this is where we had our “Eureka!” moment: The beekeeper had indeed not added queen excluders on top of the brood boxes, which may have provided a convenient hiding place for varroa mites – without any Apivar strips being present in the supers.

As we began to raise our concerns regarding lowered treatment efficacy due to possible excess brood patches in the honey supers, the beekeeper became somewhat contrite and promised to look more closely at the supers on top of his brood boxes. A day later, he confirmed to us – adding photo evidence again – that patches of brood of varying size could be found in all of the supers.

We tried to encourage the beekeeper to have more confidence in the natural seasonal cycle of his colonies in the future. More than a few new or newish beekeepers are worried when the end of summer approaches and they perceive their colonies as “overly crowded”. Maybe this phenomenon is related to the warnings and calls to attention new beekeepers often receive in the context of swarm prevention in springtime. But the focus on “adding more space to the hive”, looking out for queen cells and splitting hives to avoid swarming in spring has no meaningful implications for the status of honey bee colonies in August. At the end of summer, honey bees are already detecting the daily reduction of sun hours, and the queen starts laying the first eggs that will later develop into winter bees. Adding more space at this time of year will soon become a risky endeavor rather than a favor to honey bee colonies, as their population of summer bees is set to decline and more space will only make it more difficult to keep the colony warm in the coming months and more management work for the beekeeper.

We hope this case offered some insights regarding the role of hive management actions throughout the season and how they can potentially affect varroa treatment outcome. Even when beekeepers read product labels carefully, respect the correct dosage and treatment duration, there are still pitfalls in the arena of hive management that can directly influence the treatment outcome. In this specific case, the addition of “hidden” brood patches and space for worker bees (and varroa mites!) to avoid direct contact with the Apivar strips in the brood box would have definitely had a negative effect on treatment efficacy. While it is wise not to place strips in the supers — to avoid any risk of contaminating honey intended for human consumption — the beekeeper, in this case, inadvertently provided the varroa mites with a comfortable refuge: out of sight and out of reach of the treatment.

by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma  by Véto-pharma

by Véto-pharma