By Freddy Proni, Véto-pharma North America Area Manager

The never-ending saga of Covid-19 restrictions, the approach of this year’s unique holiday season, and the isolation some of us experience during this “pandemic” can be mind numbing. With the onset of the winter months, many of us have already treated our bees during the low to broodless state and others will treat shortly based on their region. Thankfully the winter solstice will mark an increase in day light hours, and we will undertake the winter tasks associated with beekeeping equipment building, maintenance, and preparation in anticipation of the 2021 bee year. As for 2020, it has memorable to say the least, mind boggling and profane at times, and for some of us, gave us a glimpse or a comatose existence of what it is like to be a zombie.

Each and every year recently, the media runs a story about Zombees (Zombie honey bees) as it alluringly mystifies the Halloween and the Day of the Dead experience. Many of us see the headline and the catch phrase passively; but do they really exist? Well to alter a famous holiday editorial phrase from a renowned 1897 editorial; “Yes, Virigina, there are zombees.”

As beekeepers, we are curious beings. Apiculture broadens our horizons and sparks an interest in nature, the things around us, and brings forth a refreshing curiosity which leads to observance. Many times, during the warm summer months after choking down our smokers we arrive home late in the evening. Tired, sweaty, and perfumed in smoke we often pass a nocturnally lit exterior light whose luminescence entices creatures of the insect world. We expect to see moths and a variety of other dancing insects bouncing off and diving into our human made artificial light but sometimes we may see honey bees. This is strange, as our nectar gathering friends should be in their hives, resting and performing duties awaiting the next day’s dawn and outside temperature rise. Without knowing it, you may have witnessed honey bees dancing in the evening flood lights, and never thought, that the night of the living dead was closer to home than those comic books, movies, or TV shows.

It was in 2008 at San Francisco State University, that entomologist Dr. John Hafernik collected some stumbling bees on the ground near a light source to use as feed for a praying mantis. The bees were collected and placed in a glass vial and later stored in his desk and forgotten – the vial of dead bees was later found to contain small brown colored pupae leading him to the hypothesis that the collected bees were victims of a parasite.

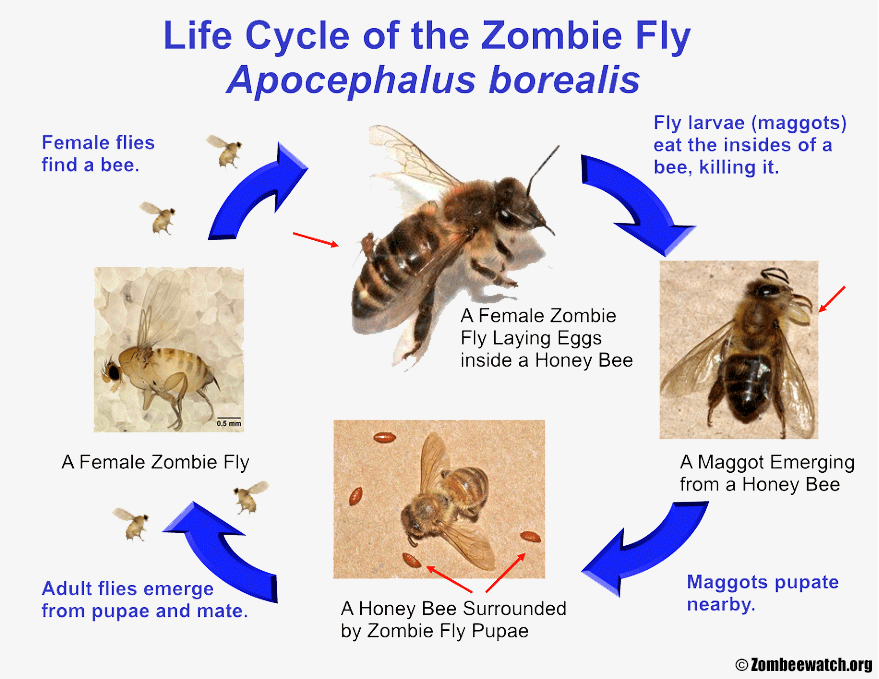

The term “zombees” refers to honey bees who have been parasitized by a tiny phorid fly (family Phoridae) known as Apocephalus borealis. Native to North America, this fly is not exclusive to honey bees, but has also been found to host on bumble bees and wasps. Very small in stature, the adult phorid fly measures between 2-2.9 mm in length and is said to resemble a small fruit fly. Thankfully this minute insect is not interested in humans as a host, nor our pets.

A mated female fly oviposits (lays eggs) into the abdomen of the honey bee where the eggs hatch inside the host. The resulting larvae then feed upon the bees’s flight muscles in the thorax and hemolymph. Eventually larvae emerge in about a week’s time from the sector between the thorax and the head of the honey bee. Pupation usually takes place for about 28 days with the pupa measuring less than 5/64” (2mm) in length resembling a slightly flattened piece of miniaturized amber to brown colored rice. Upon maturation, the adult emerges and takes flight eventually looking for a host to hijack and start the reproductive cycle again.

Although native to North America, zombees have not been found in all states. Reports have been confined to the coastal states spanning in the east from Nova Scotia Canada down to North Carolina and on the western coast from B.C. Canada through central California. Currently, A. borealis does not appear to be a threat to the honey bee industry, but through citizen science, beekeepers and the general public can take a stance to participate in documenting the spread of this parasite.

To learn more or become a citizen scientist participant, please visit https://www.zombeewatch.org/ This website offers an interactive map, sample collection information, presentations, FAQ, and how you can participate and become an active part in this cause!

Phorid flies are indeed fascinating and they exemplify that our world of apiculture is ever evolving offering new discoveries and constantly raising questions. Be it serendipity, observance, or just persistence, there are always new facets of this industry to be discovered and brought forward. For those who enjoy the macabre you may wish to spend one of these isolated evenings and check out the sarcophagus like fluid filled prepupal encasing virus, sacbrood; and the respective fungal soft and hard mummies of chalk and stone brood!

References:

Join the Véto-pharma community and receive our quarterly newsletter as well as our occasional beekeeping news. You can unsubscribe at any time if our content does not suit you, and your data will never be transferred to a third party!

© 2019-2024, Véto-pharma. All rights reserved